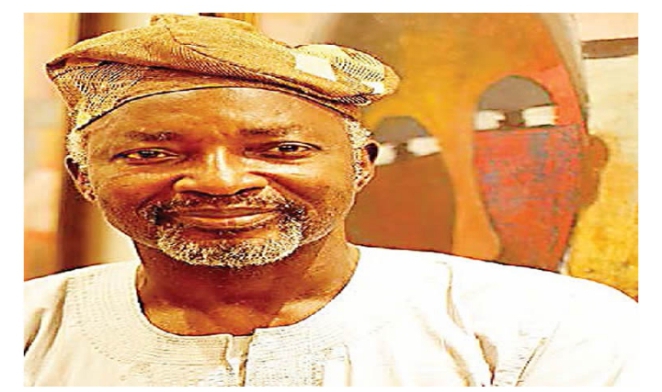

Traditional religion more peaceful than Christianity, Islam –Painter, Muraina Oyelami

Veteran visual artist, drummer and thespian, Chief Muraina Oyelami, speaks to BOLA BAMIGBOLA about his background and works

You’re a widely-travelled, renowned artist, why have you chosen to settle back in Iragbiji, rather than one of the big cities, for instance, Lagos or Ibadan?

Remember very well that Iragbiji is my hometown. Even though I left Iragbiji since I was young, I had always prayed to come back home. It is my place of birth, so, I returned because coming back home is normal. Everyone prays to return to their roots someday and that is exactly what I have done.

Was your return to Iragbiji connected to the fact that you were conferred with the chieftaincy title of Eesa of Iragbiji, which is second in command to the town’s traditional ruler?

I came back before my installation. I decided to come back home to face my artistic work. I was in Ife for 12 years before I was installed as the Eesa of Iragbiji and next year will make 30 years since I have been Eesa.

Hasn’t becoming the Eesa limited your activities as an artist, particularly as a drummer and dancer?

No, it has even enhanced my craft, though it (the demands of the position) is time-consuming. But imagine being put in a solitary confinement, you have to adjust to it in a matter of time. When I was made the Eesa, my friends and colleagues wondered how I would be able to cope. At first, it seemed like that, but thank God it has actually given me more time to be creative. Being the Eesa hasn’t negatively affected my work.

What was childhood like for you as someone born in Iragbiji?

I was born into a family of peasants. My father was a farmer, while my mother was an alarobo, or livestock trader. She sold goats, sheep and hens. My father was a devoted Muslim. I am the only surviving child of my mother; all the children she had before me died. But I have half brothers and sisters born to my father by other mothers.

Did you also start schooling in Iragbiji?

Yes, I attended Iragbiji Anglican School and St. Peter Anglican School. But despite being a brilliant pupil I dropped out in secondary school for lack of funds. I later did my A levels as an external student and then I went to Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, United States in 1974. I also studied at the University of Ife (Technical Theatre) 1978; and Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany in 1985.

How did you discover your interest in art?

I actually discovered my talent as a painter as early as when I was in primary school, which was in the 50s. I was inspired by a certain man – I can’t remember his name again. I was also influenced by various pictures of hairstyles that I used to see at the barbershop. During my childhood days, I made drawings and paintings for barbers. I did a lot of artworks then because I like artworks, but that was not at a professional level.

My musical talent came to light through orchestra music. In Iragbiji, we had local groups like High Glory Orchestra, New Jersey Orchestra, and others, who did hire me to assist during their performances. I was good at playing ‘double toy’ also known as bongos. They would hire me whenever they got invitations to perform at different ceremonies, such as funeral, wedding, christening and others. Because I just loved to play drums and I was enjoying it, I did not charge money to perform and I was never paid. But at the end of the shows, they might give me some biscuits and soft drink called Crola, which I would take back home. I was like a freelancer and it felt so great, because that inner happiness was there. It gave me pride that people recognised my talent and worth.

How did you take the decision to become a professional artist?

I cannot differentiate between when I was an amateur and a professional. In 1964, I was already with the national theatre group of Duro Ladipo. At that time, there was this Experimental Art School, sponsored by the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan. They came and sponsored a workshop which was at first conducted by a famous black American artist, called Dennis Williams. After him, there was Jacobs while the third one, which held in 1964, was conducted by the late Ulli Beier’s wife known as Georgina Beier, who was also a British artist. That was the one I participated in.

I got into Mbari Mbayo Artists and Writers Club in Osogbo. So many people came to participate in the workshop then. There were people like Twin 77, Rufus Ogundele, Jimoh Buraimoh, Jacob Afolabi and more. The experts came and selected a few of us, who they thought were very talented and that they could groom. So, that was how I started as a professional artist. I attended different art workshops both in Nigeria and overseas before I chose painting as my area of specialisation.

Which artists have had the biggest influence on you and your works?

None, because I learnt later that it is always great to be original. Be you a poet, singer, drummer, whatever, it’s not easy to be original, but you have to work towards it. You may have other people’s works that inspire you, but don’t be a copyist; just find your own level and voice. It pays to be original. People recognise me, they know whatever I do is from me. If you place my work among one million works, it stands out.

Do you miss anything or feel nostalgic about the Duro Ladipo era?

I knew Duro Ladipo from a film house in Osogbo called Ajackson Cinema, which was owned by a Korean. Duro was the manager of the cinema and was also a pupil-teacher. Besides that, he had a drinking bar called ‘Popular Bar,’ which was along Popo Street after St. Benedict Catholic Church, Osogbo. When he closed from work, he would retire to the bar to sell drinks. At the time, I was working as an attendant at a petrol station adjacent to Duro’s bar. He used to come to buy fuel. They later formed the Mbari Mbayo group and they used to stage plays. One evening, I went to the cinema to see their performance, then Duro approached me and asked me to join them because he observed that I had interest in performances, drumming and others. His words were magical and there and then I left my otherwise lucrative job as a petrol station attendant and joined the group. We were not being paid salary; we survived only on whatever we got.

I was not a major actor in the theatre, when I joined; I was into music and that was how I got to know more about dundun drumming. The late Timi of Ede, Oba Adetoyese Laoye, who was a close friend of Ulli Beier, inspired me a lot. I was not that visible on stage like Demola Onibonokuta, who played Gbonka in Obakoso. I rather loved and concentrated more on music than acting. I got my nickname, Kamran, from Ajackson Cinema.

Later, I learnt from more experienced drummers how to play other drums. I learnt bata drumming from Ayantunji Amoo, who starred in Saworoide. We used to perform weekly on the Western Nigeria Television Service. With the group, we travelled to Germany for the Berlin Festival in 1964, precisely Western Berlin, to perform Obakoso, which is the story of Sango. The following year, we attended the first Commonwealth Art Festival in Britain. We toured England, Scotland, Wales and later, our agent organised a tour of Europe for us and we went to Belgium, Austria, Sweden and Switzerland before we returned to Nigeria. When we came back, I left the theatre group because at that time I was busy doing my visual artworks and I felt like being on my own.

You’re an artist of many parts – drummer, dancer and painter. How have you been able to divide your time among the three to the point that you’ve achieved excellence in the three?

I do deep etching, which is graphic, linoleum cut, wood print making, and I attempted carving too, but my major artistic area is painting on canvas or on board and that is what I am still doing till now.

I appreciate the rhythm of music, I can move but I can’t call myself a dancer. I am a drummer and I love Yoruba music. I have given lecture demonstrations to people and institutions. I taught Yoruba music at the University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University and I wrote two books on Bata and Dundun drums. I used them to tell the story of my race to the outside world.

Is it true that there is a mystical dimension to the talking drum and bata, beyond being entertainment instruments?

If anyone thinks there is something mystical about them, it is because they look upon the players as beggars. They (drummers) are doing a great job, because they are like therapists, whose performances do a lot of good things to the heart of the people. But ironically, people tend to look down on drummers as beggars. I don’t believe there is anything mystical about the drums.

Your paintings are quite colourful and mostly have abstract figures. What philosophy drives them? Do you have a name for the style?

I have done a lot of paintings that are realistic, but I have come around some notable artists, who willfully chose to do abstraction. It is not a taboo to do something that is rarely known. I chose my area of specialisation because I want to make my work more interesting. Before I can show my works to people I must have first admired what I have come up with.

What exactly inspires your works mostly?

First and foremost, I can be moody. People and places have been my source of inspiration and basic area of interest. Also, there is what I call ‘crossover’, which means, one that has no preconception, something that comes by itself and it will take me some time to even know where it is coming from and what it is. These are my ways of working. There is no premeditation in what I do.

It’s on record that you’ve had several exhibitions, including outside the country. Can you remember exactly how many and which one holds most enduring memories for you?

I cannot tell the number of places I have had exhibitions because they are more than I can remember now. But among the big exhibitions I have done is the one we had long time ago at a museum in Washington DC (United States). I also remember the early exhibition I had in 1967 at the German Cultural Centre in Lagos. Our first exhibition was in Osogbo and I remember that the late Ataoja of Osogbo, Oba Adenle, was the guest of honour. He looked up and admired the works and later on, he donated the first floor of his palace to myself, Rufus Ogundele and Bisi Fabunmi, to use as our studio and we used the place as our studio for years. Oba Adenle was a progressive Kabiyesi.

When do you consider the turning point in your career?

I have been doing the same thing that I was doing before. I was a visual and performing artist when I joined Duro Ladipo’s group and I am still one up till now. There was no turning point except that people know me more and I have time to concentrate more on my work and it was during this time that I went to Ife for another 12 years of working and creating.

At what point did you become a lecturer in OAU?

I was at Ife between 1976 and 1987 and Professor Akin Euba was my Head of Department. During this period I never had a full-time lecture period. In a week, I might likely not have more than four periods. So, I used the free period for my artistic work. In fact, I used my office then as a studio. So I had enough time to do both.

Why did you quit the lecturing job?

I left because there was no more fun; it was getting boring. I felt I was being underutilised and also because the man I came to work with had already left Ife for Lagos. In fact, Dr Adegbite, who was our Head of Department then, asked me why I wanted to withdraw from the lecturing job. It was that same month that I had an invitation to participate in the Festival of Arts in Scotland and since that time, I have been busy.

You had a very impressive performance in Kunle Afolayan’s Figurine. Have you featured in other movies after that?

I have featured in so many other movies apart from Figurine by Kunle Afolayan.

You described your father as a devout Muslim and you bear a Muslim name. Are you still one?

If I have to have a religion, then I will go for traditional religion because it is peaceful and there is no antagonism among them unlike the other foreign religions. I am not a traditionalist; I am alone with my God. If I want to believe in anything I believe in Olodumare, which is the Yoruba word for God. I have no intermediary between myself and my God.

I respect our traditionalist because that is the closest ally that I have and can relate to but that doesn’t mean that I am a member of their cult. My God has always been there for me and He has never disappointed or left me alone and I am okay like that. So, I have no religion, if I may say.

But you must have practised Islam as a child, having been born a Muslim. At what point did you decide you would have no religion and what was the reason?

Well, I can’t quote any date but when I grew up, I discovered that there is no ethnic group or nation that doesn’t have a name for Almighty God. For us, the Yoruba, God is called Olodumare; and God or Allah or Olodumare has no specific worshipping state or place. You can worship God anywhere. And also, God has no gender, nobody knows Him and nobody can say this is the figure or likeness of God. God is in you; you do not see Him physically and I don’t need any intermediary between myself and God because he is omnipresent and omnipotent. I just believe that I have to deal directly with my God. Maybe I can say I discovered this after I had visited a lot of worship places.

During the Ramadan period, I try to observe the fast but most of the time I find myself eating secretly before the appropriate time to break the fast. I am also an ulcer patient, but of course I got rid of it through a surgical operation around 1980 or thereabouts. So, under that guise, I told everybody that I could not fast anymore because I am a survivor of ulcer.

Apart from all these, I have studied the formation of religions, which are so many in the world and I found many of these so-called religious people to be unholy even though they claim to be holy. But many people need them and I also like it when they preach. They preach peace and harmony and that is what God wants. But I don’t need to bow down to any man or woman and look at him or her as holier than thou because we are all human beings. I respect them a lot but I should be left alone.

Do you sometimes have Muslims trying to convince you to return to Islam?

Nobody really knows me as a Muslim. But there was a time they did and I also told them that I am not an Arabic speaker, so if I can’t pray to my God in the mosque in Yoruba language, then I don’t see the reason why I should be going to mosque. That is another good excuse, I think (laughs).

You have a daughter, Bimpe, who is also a dancer. You must have influenced her. Was it directly or indirectly?

Maybe she was influenced by me, but not directly. I have known it from her childhood that she is a talented singer and dancer. I have done a lot with her and I have taken her to places but I didn’t mandate dancing for her. She saw what I was doing and she became interested in it and she fell in.

Is she your only child following in your footsteps?

Yes, I will say so. Others are geologist, teachers, scientist, engineer and professionals in other areas. But right from their youthful days, they were all into what I call art appreciation. They all went through that.

Where and how did you find love and at what stage of your life did you marry?

We met at Osogbo and that was when I was in Duro Ladipo’s theatre group in the early 60s. We met and we got married.

What is your daily routine like these days?

I am about to go to the studio to work before you came in. I don’t paint every day except when I am inspired. If I don’t paint, I will watch television, read books and in the evening go out to socialise, but nowadays I don’t drink anymore because of my age.

Do you still have many of your contemporaries who are still active?

Yes, we are all over the place except that we have lost some of them. Some of my contemporaries are Jimoh Buraimoh, Bisi Fabunmi and others. From our generation, I think there are only three of us left.

If you are to rate today’s generation of visual artists, will you say they are more talented?

When our generation started, we never focused on or knew that our works would sell. We were just doing things from within and were just managing and that is something that is unusual. But seeing us successful, many people then rushed to become artists because they wanted to make money through stealing of different artists’ works to form their own. They are never going to be original because they copy. The unlucky collectors who come to Nigeria just to spend a day or two often see fake works with our names on them and buy only to discover later that they have bought counterfeits.

Most of them (young artists) are just running around to make money, they are insincere because they don’t even know what they are doing, but a few of them are highly talented. I used to buy from them to encourage them.

Most recently, I established a place called AVPAI – Abeni Visual and Performing Art Institute. Abeni is my mother’s name. I named the institute after her just to immortalise her. In that place, we have empowered over 200 young people. Just yesterday, I chose three of them and empowered them with almost N1m to work on their own adire business. This is how I think I can help the young ones.

Punch